Dear Reader,

We got a letter the other day from a Mrs. Rubin, a third-grade teacher out in the sprawling cornfields west of Omaha. She’s been in the game for twenty-seven years. She remembers when a disruptive child was told, quite simply, to sit down and be quiet. It usually worked.

But times have changed. Mrs. Rubin is no longer a teacher; she’s a beleaguered factory manager in the People’s Democratic Republic of Classroom 3B. Her new production quota, handed down from the remote Politburo at the District Office, has nothing to do with long division or spelling. Her latest Five-Year Plan is a plan for feelings. And its primary instrument of production is a beanbag chair and a basket of fidget spinners in the corner of her room.

They call it the “quiet corner.” It’s the latest glorious directive from Central Planning, a therapeutic marvel designed by theorists in faraway universities who haven’t faced a roomful of eight-year-olds since the Carter administration.

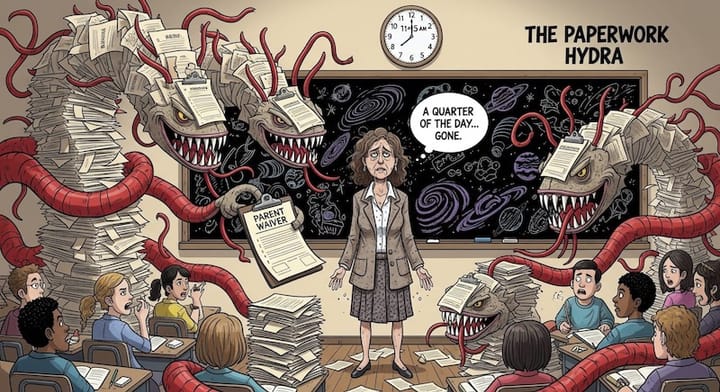

The real purpose of the “quiet corner” is not education. It is documentation. It is an altar upon which the teacher’s time is sacrificed to the god of Bureaucracy. When a student is dispatched to this corner, the real work begins… for Mrs. Rubin. She must log into the district’s online portal and fill out a Behavioral Intervention Plan (BIP) addendum and cross-reference the Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA).

She told us about her 22-minute lunch break yesterday. A boy—let’s call him Kevin—had a meltdown over a lost crayon and was sent to the corner. Mrs. Rubin sat at her desk, wolfing down a sandwich, trying to file the incident. Was Kevin’s outburst “Peer-Engaged Off-Task Behavior” or “Task-Avoidant Sensory Seeking”? The dropdown menu offered a dozen such absurdities. The system demanded she classify the crayon incident with the clinical precision of a CDC virologist. After fifteen minutes of clicking, the Wi-Fi blinked. The form reset. The bell rang. The problem that took thirty seconds to de-escalate required an hour of paperwork she didn't have.

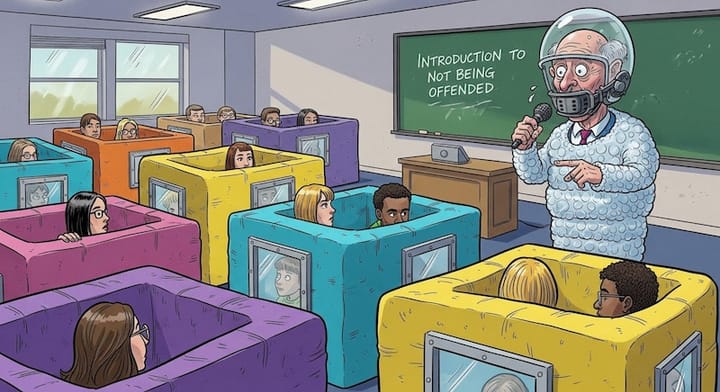

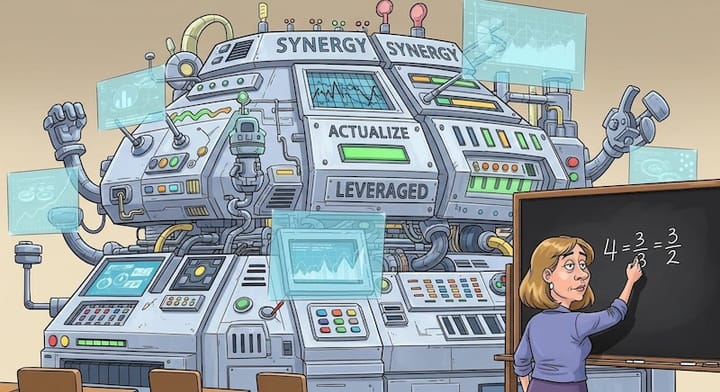

This is all part of the new language of failure: Newspeak. In the reports filed with the principal—the regional party boss—reality is carefully obscured. A child hitting another is an “unwanted physical interaction.” A temper tantrum is an “inappropriate vocalization.” The “quiet corner” itself is sanitized as the “De-escalation Zone” or the “Safe Space.” This language is not meant to clarify. It is meant to allow administrators to file reports declaring mission success while the classroom burns. “Emotional regulation opportunities were provided to 110% of targeted students,” the report will say, and everyone at the board meeting will nod sagely.

But who pays the price for this command-and-control economy of feelings?

Consider the case of two students in Mrs. Rubin’s class. There’s Maria, a bright girl who finishes her math worksheets in ten minutes, then quietly reads a book. She never causes a problem. She is the Hero of Socialist Labor, the model worker who overfulfills her quota.

And then there’s Kevin. Kevin spends, by Mrs. Rubin’s estimate, a third of his day either in the “quiet corner,” on his way to it, or actively trying to earn a trip there. Each visit generates a mountain of paperwork. Each tantrum requires a phone call to his helicopter parents, who suggest the teacher isn't “meeting his unique sensory needs.”

All of Mrs. Rubin’s non-instructional time—the precious minutes she could use to prepare an advanced reading list for Maria or challenge her with a complex math problem—is consumed by managing and documenting Kevin’s therapeutic state. The productive worker is ignored to subsidize the non-productive one. The compliant student is punished with neglect, while the disruptive one is rewarded with a universe of attention, specialists, and administrative energy. What kind of incentive structure is that?

Like all centrally planned systems, this one is doomed to fail. It is a Potemkin village of therapeutic jargon built on a rotten foundation of perverse incentives. It crushes the spirit of the frontline worker, the teacher, who knows it’s all a fraud. And it produces nothing of value, except for more administrators, more forms, more meetings.

The only thing this system is designed to grow is the bureaucracy itself. The party officials will keep publishing glowing reports about the glorious success of the Five-Year Feeling Plan, right up until the moment the whole rusty enterprise seizes up and collapses into the dust. And Maria, forgotten at her desk, will be left to wonder what it was all for.